The Lake Lock

by Ken W. Watson

|

| Narrows LockWhy is there a lock in the middle of lake? My dog is clearly puzzled about the odd location of Narrows Lock (centre of photo) - sitting between Big Rideau Lake and Upper Rideau Lake (both of which in the pre-canal era were parts of one large Rideau Lake). Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2007 |

Why is there a lock in the middle of a lake? Locks are normally situated at navigation impediments such as rapids, but such is not the case with Narrows Lock, situated in the middle of Rideau Lake. It’s a tale of disease and geology.

The original plan for this area of the Rideau Canal, which Colonel By proposed in 1827, was to construct a dam and two locks at Chaffey’s Mills, build a dam and one lock at First Rapids (Poonamalie) and excavate an open canal cut across the Isthmus (the main watershed divide between the Rideau River Watershed to the north and the Gananoque River and Cataraqui River watersheds to the south) at Newboro. The original plan for this area of the Rideau Canal, which Colonel By proposed in 1827, was to construct a dam and two locks at Chaffey’s Mills, build a dam and one lock at First Rapids (Poonamalie) and excavate an open canal cut across the Isthmus (the main watershed divide between the Rideau River Watershed to the north and the Gananoque River and Cataraqui River watersheds to the south) at Newboro.

Based on the original surveys, the dam and lock at First Rapids would raise the level of Rideau Lake by about 3 feet (0.9 m) and the dam and locks at Chaffeys would raise the water about 18 feet (5.5 m) to match that level. This would create a very large summit pond, 28.6 miles (46 km) in length, able to supply water to both sides (Cataraqui/Gananoque watersheds and Rideau River watershed) of the Rideau Canal.

|

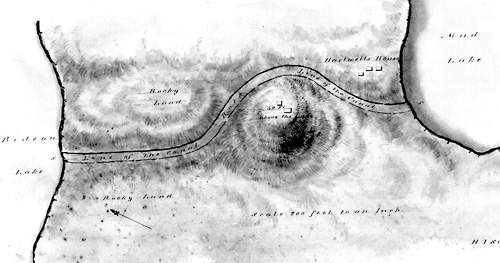

The Original PlansThe upper image (looking west - Opinicon Lake on the left, Indian Lake on the right) shows the original 1827 plan for two locks at Chaffey's Mills. The lower image (looking northeast) shows the original concept of a simple canal cut linking Mud (Newboro) and Rideau (Upper Rideau) lakes.

Upper image, section from: "Locks and Dams at Chaffer's Mills. Section 15. John By, Lt. Colonel Roy'l. Engrs., Com'g. Rideau Canal, 25th October 1827". Library and Archives Canada, NMC 21879.

Lower image: "Isthmus Rideau Lake", May 5, 1828, Scottish Records Office. |

However, by 1829 Colonel By was in trouble with his original plans. Two issues had come to the fore to thwart his design. One was malaria, which, with complications from other diseases of the day, played havoc with the workers each summer, particularly in the southern Rideau. Newboro was one of the hardest hit areas. Since the late 1700s, malaria had been endemic within the range of the Anopheles mosquito in Ontario (see “Malaria: The Secret Immigrant”). The Rideau work camps provided ideal conditions for the mosquito to spread the disease. Annually, about 60% of the workforce would come down with the disease and 2 to 4% would die. The only “hard” numbers that we have for Newboro are those for 1830 when, of the 334 men at the site, 70% contracted malaria and 4% (14) died. Its main effect was to put fear into all the men, and by 1829 men were disappearing from the sites during the “sickly season” (August to mid-September) in order to avoid getting sick. Those who were willing to stay demanded higher wages.

The second issue was the geology of the Isthmus. When surveyed in 1823/24 by Samuel Clowes, and in 1827 by John Mactaggart and John Burrows, the presence of hard bedrock was not noted. A hard rock known as migmatite underlies this area. Migmatite is a product of high temperature melting, a cross between an igneous rock and a metamorphic rock. The bottom line is that it is very hard – and, given the blasting technology of the day (black powder), it was very difficult to excavate.

In a report written by John Mactaggart to Colonel By in 1828, he writes “The oftener I examine the excavation now in progress between Rideau Lake and Mud Lake the more I am convinced that it is going to turn out to be a more difficult piece of work than has been suspected. ... I am sorry that when surveying this Isthmus last Summer we had not a set of boring tools to ascertain its nature more fully in consequence the estimate returned of this work will not I am afraid be sufficient unless some other method than the present be adopted. ...”

In addition, the rock was fractured, so as they dug down, water flowed into the works. Pumping out this water was a slow and laborious process.

In October 1828, the contractor for this site, William Hartwell, wrote to Colonel By, asking to be released from his contract: “From the nature of the Rock on my job, I now find from what I have expended, say to the amount of two thousand pounds, exclusive of what I have received from you that it is totally out of my power to fulfil my engagement at the Contract prices. Under those Circumstances and from your knowledge of the nature of the rock, may I request you will take my Situation into your Consideration, and release me and my Securities from the Contract; by so doing you will much oblige.”

Colonel By was in a dilemma. He wasn’t impressed with Hartwell’s progress and so released Hartwell from his contract. Another contractor, a Mr. Stevenson, was hired. But Stevenson wasn’t able to attract any labourers at the going rates and soon quit the job.

Colonel By needed a new solution and his first action was to take control of the job himself. He put Captain Cole directly in charge of the work at the Isthmus and raised the labour rates in order to attract a workforce. In addition “to induce Labourers who were dispirited from the place having been so extremely unhealthy in the year 1828 to return, I have accommodations built for them, and Provisions of every description provided for their Comfort, …”

But by 1829, Colonel By was again in trouble with this part of the Rideau project. The hard fractured bedrock at the Isthmus was giving him nothing but headaches. There was no way he was going to complete this section in time, so he looked for a new solution. The one he came up with was deceptively simple; if you can’t dig down, then bring the water up. But by how much could he raise the water level?

New detailed surveys of the lakes showed him that he could raise the level in the area of today’s Upper Rideau Lake by almost 5 feet (1.5 m). Colonel By was initially looking to raise the water only 4 feet (1.2 m), so this plan seemed do-able. The easiest solution would have been to add that 4 feet to the total lift at Chaffeys and at Poonamalie but this wasn’t the route that Colonel By chose to take.

The records are a little unclear on the exact chronology of the decision making. At some point prior to 1830, Colonel By had decided to go from two locks at Chaffeys to one lock stating: “Prior to commencing the Works I directed further Levels to be taken when it was ascertained that by Deepening the Bed of the River, and cutting off some Rocky points, the Rise to be surmounted might be reduced to 12 feet 6 inches, I therefore considered, that by constructing a Waste Weir in such a manner as would enable the Water in the Lakes to be duly regulated, two Locks would not be required but that one of 12-1/2 feet Lift might be placed in the Channel of the River with perfect security.”

It appears that by the time Colonel By was wrestling with the problem of bedrock at the Isthmus, his one-lock plan for Chaffeys was already in progress. So adding 4 feet at Chaffeys would make for a higher dam and higher lock gates. Colonel By felt that this extra height couldn’t be added with safety.

His second issue was that adding 4 feet at both Chaffeys and Poonamalie would flood a great deal of extra land in the areas of Newboro Lake and Lower Rideau Lake, land that would have to be compensated for. But, given that the western end of Rideau Lake (Upper Rideau) could be flooded by that amount without causing undue damage, he decided that the best course of action was to put a lock at the bottom end of the Isthmus cut and another at a narrow section of Rideau Lake known as Upper Narrows (today’s Narrows Lock). This placement of two locks would raise the level of the existing Rideau Lake in that location, creating what we know today as Upper Rideau Lake. He would save on excavation depth of the Newboro cut by the amount he could raise the water.

“I considered it indispensably necessary to deviate from the original plan, and have therefore backed up 4 feet of water by placing a Lock and Dam at the Narrows, and to surmount this additional rise, it being impracticable to raise the water of Mud Lake by increasing the lift at Chaffey’s Mills with safety, a Lock of 4 feet lift, is placed at the end of the Excavation at the Isthmus, entering Mud Lake.”

|

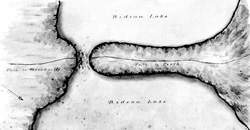

| Upper Narrows This early view of Upper narrows (looking southwest - towards Upper Rideau Lake) shows the peninsula that formed a narrow constriction in Rideau Lake - ideal for the placement of a lock, dam and weir. "Narrow's Rideau Lake", May 5 ,1828, Scottish Records Office. |

In the pre-canal era, the Narrows (then known as Upper Narrows) was a narrow channel created by a spit of land extending from the north shore of Rideau Lake to within 100 to 200 feet (30 to 60 m) of the south shore. Depending on the water levels, it was about a foot (0.3 m) deep, and was used as a ford on a trail to Perth. By 1826, the use of that ford and trail had essentially been abandoned. Upper Narrows was tailor made for the easy placement of a lock, dam and weir.

It’s interesting to note in the records that one of the Royal Engineers working with Colonel By, Lt. Edward Frome, disagreed with him. There are no records of discussions between Lt. Frome and Colonel By at the time, but in an 1837 report Frome wrote “Had the Mud Lake been raised to the same level as the Upper Rideau, by placing this lock as an addition to that at Chaffey’s Mills, and the lift of 4 feet 10 inches of the Narrows added to that of 6 feet 4 inches at the First Rapids [Poonamalie], the summit level would have extended the whole distance between this place and Chaffey’s Mills, about 30 miles, and the work at the Narrows have been reduced to merely deepening the old channel, or making a short cut across the tongue of land. Some low ground must of course have been flooded by this plan, both on the shores of the Lower Rideau and Mud Lakes, but it is of little value, when compared with the saving it would have occasioned.”

|

| Narrows LockThis 1830 map (looking south) shows the plan for the lock at Narrows. The weir (water control dam) would be placed close to the original Narrows' channel. "Survey of the Upper Narrows Rideau Lake & Plan of Lock" by John By, March 18, 1830. Library and Archives Canada, NMC 12892 52/80. |

Colonel By did envision that his plan might be changed in the future, not by raising the water at Chaffeys and Poonamalie, but by deepening the cut at Newboro. To this end he built the locks both at Newboro and at Narrows without breastworks (upper foundations). This would allow them to be easily converted into guard locks (non-lift locks). “And should it be found advisable at any further period, on the Country becoming more healthy, to deepen the said Excavation, as originally proposed, it can be done, and there being no Breast Works to the Two Locks above mentioned they will then Serve as Guard Locks.”

Although the cut at Newboro has been deepened over the years, the area has never reverted to By’s original plan of having an open waterway between Chaffeys and Poonamalie. The only other change in the area is that over the years, the height of the dam at Poonamalie has been raised, reducing the lift at Narrows from about 4.8 feet (1.5 m) in 1832 to 2.5 feet (0.8 m) today.

So, now you know why there is a lock in the middle of a lake. Narrows, the “Lake Lock,” continues to operate today – the dam and weir at this location maintaining the level of Upper Rideau Lake. It’s a testament to Colonel By’s skill at adaptive engineering – coming up with a unique, very successful solution to a problem brought on by disease and geology.

Sources:

Frome, Lieutenant Edward C., “Account of the Causes which led to the Construction of the Rideau Canal, connecting the Waters of Lake Ontario and the Ottawa; the Nature of the Communication prior to 1827; and a Description of the Works by means of which it is converted into a Steam-boat Navigation”, in “Papers on Subjects Connected with the Duties of the Corps of Royal Engineers”, London, vol. 1, 1837, pp. 73-102.

Price, Karen, “Construction History of the Rideau Canal,” Manuscript Report 193, Parks Canada, Ottawa, 1976 - digital edition, DB193, Friends of the Rideau, 2008.

Watson, Ken, "Tales of the Rideau" story “Malaria: The Secret Immigrant,” Elgin, 2010

|