The Dead Lock

by Ken W. Watson, 2015

There is a local legend in the Opinicon Lake area that the original route for the Rideau Canal was not from Opinicon Lake through the Davis Rapids to Sand Lake, the route it follows today, but rather through Hart Lake, located at the head of Deadlock Bay. Evidence for this is in the form of a lock started but not completed, a so-called "dead lock." There is a local legend in the Opinicon Lake area that the original route for the Rideau Canal was not from Opinicon Lake through the Davis Rapids to Sand Lake, the route it follows today, but rather through Hart Lake, located at the head of Deadlock Bay. Evidence for this is in the form of a lock started but not completed, a so-called "dead lock."

The exact origin of this tale is lost to history. The Dead Lock is a small canyon in the channel near the head of Deadlock Bay with vertical walls that may have looked man-made to some, leading to the idea that it was the start of a lock. That idea of a manmade structure may have been reinforced by the presence of large stacked stones near the outlet of Hart Creek, perhaps for a dam associated with the Dead Lock or even another lock.

Whatever the exact origin, the story took hold and became the truth for some. So much so that the bay on Opinicon Lake at the mouth of Peterson Creek was officially named Deadlock Bay in 1968. Many who know the story of why the bay was given that name believe that this was the original route for the Rideau Canal, that Colonel By started to build a lock here and then changed his mind, leaving a Dead Lock. Even though the story is a tall tale, their belief that it is canal related does hold kernels of truth for both dead locks. There is also truth that this was the original navigation route from Kingston to Opinicon Lake, but not for a canal.

The Facts Behind the Dead Locks

Since both sites have a fascinating backstory, both those stories will be told. The actual Dead Lock, the small canyon in Peterson Creek, will be referred to in this tale as the Lower Dead Lock. It has more the appearance of Rideau weir than a Rideau lock, but Dead Weir doesn't quite have the same ring to it. However, one can see how someone coming across this might think it was man-made. The idea that it is a man-made structure is reinforced today by the presence of piled up stones on the upstream side of the constriction.

The Upper Dead Lock, while not the root of the original tale, does have a great backstory, one that actually ties into the building of the Rideau Canal. It's the site I originally pegged as the Dead Lock since I knew the origin of the Lower Dead Lock and never thought it as the source of the story since there was no apparent mystery to it.

And while no canal was ever planned for this area, it is part of a canoe route that was used by natives travelling to and from Lake Ontario at Kingston (the mouth of the Cataraqui River) prior to the watersheds being changed by millers and then by the builders of the Rideau Canal.

So, three backstories will be told, one about the original Dead Lock, one about the Upper Dead Lock, and one about the original native canoe route that went through Hart Lake. We'll start off the story behind the original Dead Lock, the Lower Dead Lock.

The Lower Dead Lock

|

The Lower Dead Lock (looking northwest)

This constriction in the creek channel at the head of Deadlock Bay, with its vertical rock walls and man-made piles of stones may have looked to some to be a lock started but never completed, a dead lock.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2004

|

|

| The Dead Lock, 1926

This "Dead Lock" appears on this 1926 map of Opinicon Lake at the Lower Dead Lock location. Hunters Bay on this map is today's Deadlock Bay. The name was clearly well enough known at the time to merit its inclusion on this map. Crop of: "Rideau Canal Plan of Opinicon Lake", 1926, Parks Canada Rideau Canal, Smiths Falls, Engineering Map Collection."

|

The story of the Lower Dead Lock is one of geology, mining and milling.

Lower Dead Lock - the Geology Story

The simplest story is the geological story, of how moving water carves rock. Prior to a dam being raised at the location of today's Davis Lock, first by a miller in about 1820 and then by canal construction crews in 1831 (detailed below in the story of the Upper Dead Lock), Opinicon Lake was about 10 feet lower than it is today. There was no Deadlock Bay, the edge of Opinicon Lake was located at the foot of today's bay.

The area of the Lower Dead Lock had running water passing over it, Peterson Creek (aka Hart Lake Creek or Loughborough Lake Creek) flowed through this spot, eroding away any rock in its path. The area is underlain by gneiss, a hard metamorphic rock. While softer rocks tend to erode by being worn down bit by bit, sections of hard rock in this area erode by fracturing, water penetrating planes of weakness and breaking them off (either by the water directly or though frost action). This appears to be the case with the Lower Dead Lock, a more resistant section in the gneiss that originally formed a barrier for the creek. Flowing water is relentless and over centuries it found a way though the barrier, opening up fractures, allowing larger sections of rock to spall off, fall into the bed of the creek to eventually be eroded into gravel and washed into the bed of the lake. It created a small canyon with vertical rock walls.

Hart Lake is fed by two lakes, Crow Lake and Loughborough Lake. The confusion of the name of the creek flowing out of Hart Lake is a determination of which of the inlet creeks provides the greatest water contribution to Hart Lake. A naming convention for the geographic name of a lake's outlet creek is an assumption that it is a continuation of the main inlet creek for the lake. The creek flowing from Crow Lake into Hart Lake is called Peterson Creek. The creek flowing from Loughborough Lake into Hart Lake is called Loughborough Lake Creek. The official Canadian geographic map, National Topographic Map 31C/9, shows the outlet creek as Peterson Creek. The hydrographic chart (Chart 1513, Sheet 3) shows it as Loughborough Lake Creek. I personally prefer the 1926 map which calls it Hart Lake Creek, but that never made it as an official geographic place name. So, it will be referred to in these stories as Peterson Creek.

Peterson Creek has flowed from Hart Lake for at least 12,000 years - ever since Lake Iroquois (a very large glacial lake version of Lake Ontario) drained from this area. Prior to this glaciers covered this area with ice to a height of about 1.5 kilometers, depressing the entire landscape by about 575 feet (175 m). When the glaciers retreated, the topography rose back up, a process called "isostatic rebound," which is still happening today although now at very slow rate - about 3 mm (0.12 in.) per year.

Continental glaciation simply covered existing topography, so the creek was likely present before the last glacial period, hence the "at least" 12,000 years. Prior to the Davis' Rapids (the outlet of Opinicon Lake) being dammed, there were rapids at this spot on Peterson Creek, turbulent water plunging into a deeper pool at the foot of the rapids. It would have been quite evident that this was a natural feature, similar to other water carved canyons in the region.

When the first mill dam was built at Davis' Rapids in about 1820, it raised the water in Opinicon Lake by about 6 feet. That new level of Opinicon Lake would have partially flooded today's Deadlock Bay and put water to about the foot of the Lower Dead Lock, perhaps even flooding part of it. When the canal dam was completed at Davis in 1831 it flooded the lake by about 10 feet. This now put a depth of water into the Lower Dead Lock, making it look more lockish than rapidish. So the building of the Rideau Canal did in essence create the Dead Lock.

That's the simple geological story, a natural canyon that, with a depth of water sitting in it, could be interpreted to look a bit like a lock. Now for the more complicated story.

|

The Dead Lock (looking south)

The vertical rock walls of the Lower Dead Lock are a result of

spalling along fracture lines in the rock.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2015

|

Lower Dead Lock - the Mining and Milling Story

There are stones piled up on both sides on the upstream side of the Lower Dead Lock, clear evidence of human activity. What are those rocks doing there? We know they aren't part of an old lock so what was their purpose? To answer that question we have to jump to the mid-1800s when two things happened. One was the arrival of a miller by the name of James Hunter and the second was the discovery of the mineral apatite in this area.

|

Geology of the Opinicon Lake Area

This geology map shows the main mines for Apatite (Ap) and Mica (Mi) in the vicinity of the dead locks. The rock unit (brown on the map) that hosts most of the phosphate deposits is "Paragneiss, pelitica and psammo-pelitic schists and gneises. A portion of the road which crosses over the Lower Dead Lock is shown on this map. Crop of: "Geology Map 2054, Gananoque Area", 1963, Ontario Department of Mines."

|

Apatite is actually a series of minerals with similar characteristic such as Fluorapatite, Chlorapatite, and Hydroxylapatite. It is the most common mineral of the phosphates group, rocks that contain phosphate of which phosphorus (as PO4) is the main component. Phosphorus is a key element required for the growth of plants. In the 1860s Apatite was mined for its use as fertilizer with markets mainly in England and Germany. It is most commonly referred to as Phosphate mining.

Quite a bit of this went on in the Frontenac Axis, the area of Pre-Cambrian (very old) rocks that extends on the Rideau Canal from Kingston Mills to Rideau Ferry. Geological conditions were favourable for the formation of concentrations of apatite. Those same conditions are also favourable for the concentration of mica, and many mica mines in the region started off as phosphate mines.

The differentiation between a phosphate or mica mine and prospect pit can be problematic since the main exploration method was to dig pits in likely areas along the strike (direction) of the veins that hosted the apatite. A pit a few feet deep was clearly just for exploration, but once it got beyond a few feet and started to extract apatite, they were really mining. In the area to the west of the Lower Dead Lock are all sorts of pits, many small, but a number were in fact mines. All the mines in this region are what would be termed small scale mines.

Going back to milling, James Hunter, set up a sawmill on the drainage from Lower Rock Lake, likely sometime in the 1850s. He wasn't the first to locate a mill on this site, sometime around 1832 the Brewers Mill occupied this site and by 1841 a fellow named Mathewson was operating a sawmill here. All that is known about Brewers Mill is that it is located on this spot on an 1833 map (Bolton, 1833 - see the Upper Dead Lock section below for a view of that map). Same goes for Mathewson, his name shows up in this location an 1841 map (Burrowes, 1841) with a sawmill located here and also at the old Drummond Mill site at the outlet of Hart Lake. By the 1860s, Hunter built up quite an impressive sawmill operation.

Now for the secret of the stones on the upstream side of the Lower Dead Lock, they are what remains of the abutments of a bridge, a bridge that spanned Peterson Creek. A road went from the bridge to the Hunter Mill site and then over to the Opinicon Rock Lake Mine. In fact the bridge is still shown on the current hydrographic chart (even though it is long gone) as well as a portion of the original road. That road and bridge is also shown on other maps such as the geological maps of the area.

It is not clear who built the original road and bridge. Hunter operated from the lake, using steamers and barges, he didn't particularly need a road so it is suspected that the road was built sometime after mining started in the area. But it's possible it was built for Hunter's operation which would date it to the 1860s or so. The road (an extension of today's Deadlock Bay Road) and bridge provided a connection to the mainland. If it was built for mining then it would date to the 1870s or 1880s. It was certainly in place by the late 1880s since it shows up on a map dated to about that time period. One branch of the road on that map leads down to a dock on Opinicon Lake labelled "Present Phosphate Wharf," so it was clearly used to as a haul road for the ore.

The first mining in this specific area appears to have been done in 1870 by Alexander Cowan who opened up a mine that fall on Concession XVII, Lot 1 of Bedford Township, the lot owned by miller James Hunter and on which he had his sawmill. It was noted that in the first year of operation, the mine produced 549 tons of phosphate. The ore was hauled to wharf about half a mile from the mine and then shipped out by barge. Local Opinicon farmers were also getting in on the action with small shipments of phosphate made in 1871. Cowan's mine was briefly re-opened in 1892 and that was the last mining activity on that spot.

In the end there were a number of mines of varying sizes in this area. The largest mine in this spot may have been the Opinicon Rock Lake Mine, in operation in the late 1880s. A quote from the 1920 report, "Phosphate in Canada" (page 50) provides the best description:

"Concession XV, lot 21 [Storrington Township] – Known as the Opinicon, or Rock Lake mine and worked during 1891 and 1892 by the Kingston Phosphate Company, of Montreal, and by Mr. James Bell of Arnprior, under royalty to the Canada Company of $2 per ton. Mr. Bell had previously mined on this property during 1888 and 1889, and extracted about 500 tons of mineral. A force of 25 to 30 men was employed, and work was conducted by day and night shifts. Two pits were sunk, the larger reaching a depth of 225 feet on an incline of 45°, and being 75 feet long. The vein is reported to have widened from 2 feet at the surface to 8 feet at the bottom of the main pit. From 4 to 5 tons of phosphate per diem were raised from this opening. The second pit reached a depth of 40 feet, and measured 20 x 30 feet at the surface, widening as it went down. An average of 2 tons of mineral per diem was produced from this opening. Steam was used for drilling and pumping and for hoisting from the large pit.

The phosphate produced was massive crystalline, and of a green colour, changing locally to red. After being cobbed and, in some cases, washed, it was hauled a distance of half a mile to the lake, and loaded into scows of 100-tons capacity, being then taken by water to Kingston and shipped to London and Hamburg.

The mine was closed down in 1892, and has not since been worked. The total amount of phosphate produced from this property would amount to about 1,500 tons."

Inside the Opinicon Rock Lake Mine

Not much is left of the old mine. Originally sunk to 225 feet on the incline it is now flooded at a depth of about 50 feet.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2004 |

The hard rock mining of apatite basically ceased by the 1890s. Open pit phosphate deposits, discovered in Florida in 1890, providing a much less expensive source of phosphate. Some mines in the area that had economic mica associated with them changed to mining that product, but there is no evidence that this happened in the area near the dead locks.

After the mining and milling, this area was used for farming. A fellow by the name of "Admiral Horatio Nelson Sharp" bought the property from the Hunter Estate and started the Opinicon Ranching Company. In about 1919, Sharp sold the property to the Wright family who continued farming the land for some time. In 1989 this 315 acre property was purchased from Opinicon Properties Ltd by Queen's University. It was named the Cape-Sauriol Environmental Studies Area in 1990 in honour of Brigadier General John M. Cape, who made a generous donation towards the acquisition of the land, and Charles Sauriol, who played a crucial role in the fund raising efforts.

The bridge must have been maintained for some time and then presumably fell into disrepair and fell down or was removed.

The Upper Dead Lock

|

The Upper Dead Lock (looking southeast)

These large stones located near the head of the Peterson Creek may have had the appearance to some of the start of a lock.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2015

|

The story of the Upper Dead Lock does in fact start with the building of the Rideau Canal, beginning with the failure of the original contractor to complete the lock and dam at Davis' Rapids. The Rideau Canal was built by independent contractors who bid on each job and then were responsible for organizing their own crews. The design of each lock was done by the Royal Engineers but it was up to the contractor to execute those plans.

Davis Lock was a typical situation, in the pre-canal era the location was a set of rapids connecting two lakes, Opinicon and Sand. In about 1820, Walter Davis Jr. dammed the rapids using an angled log timber dam and built a sawmill. When this part of the canal was being designed in 1827, the plan for Davis' Rapids was for an overflow dam and single lock.

Davis was briefly contracted by Colonel By to find suitable local stones to build the lock and dam, but he apparently didn't do much in that regard and was let go. Davis did profit from the canal since Colonel By ended up buying his mill for £700 (approx $800,000 today) in order to construct the dam and lock in that location.

In October 1827, Donald McLever was awarded the contract to build "a Lock of 9 feet lift and a Dam of 15 feet high" at Davis' Rapids. Donald was apparently an interesting fellow and a bit of an inventor, at one point designing his own pumping system for keeping the lock pit free of water. However he wasn't a good businessman and in 1829 he declared bankruptcy and quit the job.

A traveller along the Rideau in February 1830 noted:

"The first contractor for this job [Donald McLever] like many others on the line from some mismanagement in taking the work at too low a rate was obliged to relinquish, and it is now under the joint direction of Mr. Drummond and a Mr. Haggart who will be mentioned hereafter. The first contractor seems to have had some confused idea that in all works the saving of labour constituted gain – for this purpose he has erected a pump drove by a water wheel to clear his lockpit of water. How far this succeeded is unknown, it does not appear to be in operation at this time. There is however something ingenious in the contrivance and nothing impracticable in the principle if properly applied."

McLever's departure left Colonel By in need of a new contractor. He turned to contractors who were doing a good job at other lock sites and offered them the job. At Davis a new contract was awarded to a partnership of John Haggart, the contractor building Chaffeys Lock and Robert Drummond, the contractor building the locks and dam at Kingston Mills.

Drummond, a resident of Kingston, was quite the entrepreneur. He had irons in many fires including the steamboat business. By all accounts he was a shrewd businessman and a very good contractor, so good in fact that he was one of only five Rideau Canal contractors awarded a silver cup by Colonel By in 1831 for a job well done. It was Drummond's steamboat "Rideau" (nicknamed "Pumper") that took Colonel By on the very first full steamboat transit of the Rideau Canal in May 1832.

Drummond would have of course visited Davis Lock many times during construction. Always looking for opportunities, he would have scouted the surrounding area. At some point he must have discovered or been alerted to the rapids at the outlet of Hart Lake, the head of Peterson Creek. The creek flowed from Hart Lake into Opinicon Lake, a much smaller lake back then. Originally there was no Deadlock Bay, Opinicon Lake in the pre-mill era was about 10 feet lower than it is today. The bay, or at least a portion of it, initially formed in about 1820 with the building of Davis' mill dam. Then it took on today's form when the canal dam and weir at Davis were completed in 1831.

Peterson Creek was very well known to local natives. The area between Upper Brewers and Jones Falls (specifically from the Round Tail just upstream of Upper Brewers to Dean's Island in Whitefish Lake) was not navigable in the summer. This meant there was no water connection between the southern pre-canal Rideau Lakes (i.e. Sand, Opinicon) and the Cataraqui River as there is today. The native canoe route from Kingston to the Rideau was up the Cataraqui River to its headwaters in Loughborough Lake (today's Battersea) and from there to Opinicon Lake via Hart Lake. Henry Wright recalls his father telling him that there was "an established Indian trail to the Cataraqui River through Hart Lake to Loughborough Lake thence by portage from Battersea to Dog Lake." It was only after a miller dammed the outlet of the White Fish River (which flowed from Jones Falls to Lower Beverley Lake), near today's Morton, in about 1803, that this section (Whitefish, Little Cranberry and Cranberry lakes) of the Rideau became navigable by canoe (details about this can be found in the section titled "The Original Navigation Route" below)

What caught Drummond's attention though was not the creek as a canoe navigation route, but the rapids at the head of the creek, the outlet of Hart Lake, a fall of water that held the promise of generating power. This was long before the discovery of electricity and inventions that harnessed it to power machinery. Although steam power was being developed, the least expensive way of harnessing power was to use what nature provided, moving water, with the use of a waterwheel.

Drummond would have been very familiar with this. His primary lock construction site, Kingston Mills, was the location of the very first mills on the Rideau system, the "King's Mills" – built by the government in 1784 to saw lumber and grind settlers' grain. By the time Drummond arrived there to start lock construction work in 1827 there was still one mill, a sawmill, the third one built in this location, in operation. That sawmill used a waterwheel, driven by the fall of water at Cataraqui Falls. Drummond would have seen the waterwheel and machinery in the sawmill many times.

At some point between 1829 when he took over the job at Davis and 1832, he found or was told about the drop of water at the outlet of Hart Lake. It was on a Crown Reserve (land not granted to loyalists but held in reserve for government use). He would have applied for a "mill seat," a government license to use the water power at that location. Once he had that he could then build a mill on the site.

Mills in that era were fairly simple affairs. The waterwheel consisted of either paddles or buckets and turned with the force of water against the paddles or weight and force of water in the buckets. A belt (or series of belts) connected machinery such as saws and grindstones to the rotating power of the waterwheel. The simplest sawmill used a vertically mounted crosscut (straight) saw to cut logs into planks. Later, more efficient circular saw blades were used.

Early millers such as Walter Davis Jr. lugged the required pre-made parts of the mill such as the saw blades, pulleys and parts for the water wheel to the mill site and then build the rest of the mill using local wood. Trees at the time were chopped down using axes (not saws). These were used to make a simple framework for the saw. A dam would be built and the water wheel assembled. Once the saw was in operation the miller could then start to saw planks to frame in the mill and make other improvements.

At Hart Lake, to take advantage of the drop of water coming out of the lake a dam was needed to impound the water and direct the flow to the waterwheel. Dams of the era took many forms depending on the local conditions. At Davis Lock for instance, Walter Davis Jr. built an angled timber dam – the force of the water helping to hold the dam in place. We know this since we have an 1831 drawing showing exactly what Davis' mill dam looked like. Drummond and Haggart used it as a coffer dam for the building of the canal dam at Davis Lock.

|

The Dams at Davis' Rapids

The log dam on the left is Walter Davis Jr.'s mill dam originally built in about 1820. The dam on the right, consisting of two wall of cut stone, with clay puddle in the middle and covered by earthen rubble, is the canal dam built by crews working for contractors Robert Drummond and John Haggart. Davis' mill dam was used as a coffer dam (water blocking dam) for the construction of the canal dam. Burrowes, Thomas, “Rough Plan of the Lock, Dam &c. at Davis' Mill” n.d., Library and Archives Canada, NMC 130287.

|

At Hart Lake this type of simple dam couldn't be used due to the geology of the site. The log dam built by Walter Davis Jr. was ideal for a site such as Davis Rapids which had a soft gravel bottom. However, at Hart Lake the water at the outlet flows over solid bedrock. This leads to a bit of a problem given the evidence today. At the outlet to Hart Lake there are the remains of not one, but two dams. The Upper Dead Lock appears to be the remains of a stone abutment for some form of timber dam. But just above this are the remains of what was likely a timber crib dam, timber framing filled with rubble stone. We know the origin of both dams, the earliest dam on the site was the Drummond dam, the second dam was a government reservoir dam built much later to supply extra water to the Rideau Canal. A problem today is trying to figure out which dam is Drummond's and which is the government reservoir dam.

In the Rideau Corridor by the mid-1800s, so many trees had been cut down to create farmland that it changed the character of the watershed. Flow from rain was no longer held back by forests to be let out slowly over time into the Rideau Canal, but rather quickly drained or evaporated from open farmland and was gone. So the water control system developed by the Royal Engineers, which worked very well for the first few years, was no longer working as it should, more water was needed later in the season. This led to the creation of reservoir lakes, lakes in the watershed that could be dammed so that more water could be impounded, providing additional flow into the Rideau as summer progressed. Many of these "reservoir lake" dams still exist today as part of the Rideau's water control system.

Two lakes feed water into the southwest end of Opinicon Lake – Hart Lake and Lower Rock Lake. The outlets of both lakes were the sites of early mill dams. The mouth of the creek flowing from Lower Rock Lake was originally the site of the Brewer Mill, perhaps built at about the same time as the Drummond Mill (it shows up on an 1833 map). Sometime prior to 1860, James Hunter took over that site and built his own mill and dams. Today that site is commonly known as the Hunter Mill site.

|

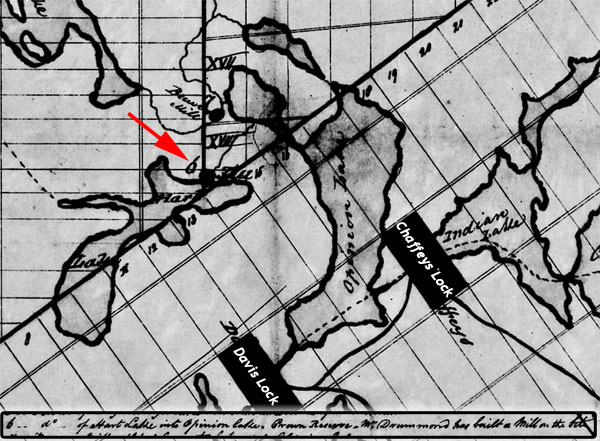

1833 Map Showing the Drummond Mill

The Dead Lock is No.6 on this map (red arrow) with the legend entry showing "Outlet of Hart Lake into Opinicon Lake. Crown Reserve. Mr. Drummond has built a mill on the site." Just above it on the map is another mill labelled Brewers Mill, located on the site of the later Hunter Mill, taking advantage of the water draining from Lower Rock Lake.

Bolton, Daniel, Captain, Senior Royal Engineer Rideau Canal, "No. 4. Diagram of the Townships through which the Rideau Canal passes from the Narrows to Brewers Upper Mill shewing the Lakes which falls into the same", 28th Oct., 1833, Library and Archives Canada, Microfiche 21772.

|

The government saw both Hart Lake and Lower Rock Lake as potential reservoir lakes. The first reservoir dam in this area was the Hart Lake dam, built by the government in 1872 at the long abandoned mill site at the outlet of Hart Lake. By the 1880s, Hunter's mill was no longer in operation and he sold his rights to the water control of Lower Rock Lake to the federal government (the Rideau Canal) in 1885. His dam near the outlet of Lower Rock Lake was re-constructed in 1889 to be used as a water control dam for the Rideau Canal. The government reservoir dam at Hart Lake was also rebuilt at that time.

At Hart Lake, it is speculated that the timber crib dam was the government reservoir dam – a very simple type of dam to construct. This type of dam was built at other reservoir lakes in the region. The dead stones make more sense for a mill which would be positioned at or near the foot of the rapids to maximize the vertical height of water on the waterwheel (the "head" of water). The government reservoir dam makes more sense near the top of the rapids in order to maximize how much water was impounded per vertical height of the dam.

The government reservoir lake dams such as those at Hart Lake and Lower Rock Lake benefited the Rideau but they didn't benefit local farmers who now found some of their farmland flooded. In the case of the Lower Rock Lake dam, a local farming family, the Teeples, didn't like the dam. They expressed their displeasure to Alfred Forster, the Lockmaster at Davis Lock who was also in charge of maintaining these reservoir dams. According to Forster, the Teeple brothers threatened to tear down the dam. And, three months after it was built in 1889, that's exactly what happened, and according to Forester the Teeple brothers were bragging that they had done the deed. Although the Teeples and another local farmer, T. O'Brien were investigated, there was no solid evidence that they were the ones who destroyed the dam and no successful prosecution was made.

One of the reasons that the government wanted to prosecute those who had destroyed the Lower Rock Lake Dam was that the Hart Lake reservoir dam faced the same risk. It was too remote to be properly protected and the same issue of flooding of farmers' lands existed. If local vandals could get away with destroying one dam, it would embolden them to do the same to the Hart Lake dam. And that's exactly what happened. At some point after the Lower Rock Lake Dam was destroyed, someone destroyed the government dam at Hart Lake. Henry Wright recollects a conversation with a local farmer, Orman Baxter, who remembered the dam, and told him that "someone took some dynamite and blowed it up".

|

Government Reservoir Dam

This photo, looking west across Peterson Creek near the outlet of Hart Lake, shows part of what remains of the upper dam, piled pieces of rubble stone. You can also see rubble stones in the foreground of the photo, on the west side of the creek, in line with a large outcrop on that side. It is presumed that these stones were part of a timber crib dam erected by the government to impound more water in Hart Lake. Note that there are very few rubble stones in the creek bed (centre) in this photo, they are all downstream, presumably pulled down, or as one local reported, "blowed up" to that location when the dam was destroyed in the late 1800s. Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2015

|

Going back to 1832/33, the stone abutments are presumed to be Drummond's dam as he had the skills and knowledge of how to move heavy stones and it would have been a dam suitable for a mill. This is where the kernel of truth to the story of the Upper Dead Lock lies – Drummond may have used some of his canal crews to build the dam for his mill.

What did the mill look like? How did it operate? We don't know. There is no evidence left on the site of the mill itself. It would have used a water wheel, either close to the dam or a bit downstream, the water channelled to the wheel using a flume. There are three categories of waterwheel depending on how much head (vertical height) and flow of water is available. There is the undershot wheel (water passing to the bottom of the wheel), breastshot wheel (water passing to the centre of the wheel) and overshot wheel (water passing to the top of the wheel). The drop at Hart Lake, given the location of the abutment stones, indicates about 6 or 7 feet – so it may have been a breastshot wheel (wheels for a mill such as Drummond's were generally 10 to 16 feet in diameter).

There are several designs of dam that could have been used. The site has not been properly analyzed by an industrial archaeologist so this is just speculation. One possibility based on what remains at the site is the use of timber to span the stream, held in place on both sides by the stone abutments. It would be somewhat similar to the design of a Rideau weir, but much more rudimentary. Squared timber could have been used, or just stacked logs with a plank front to make it watertight. This type of dam becomes more problematic the longer the span (water pressure will break the timber), but the span needed on Peterson Creek at the dam location no more than 20 feet (or less depending on the original configuration of the abutment stones). Wooden bracing against the rock bottom could have also have been used to support the dam.

|

The Presumed Drummond Dam

The top photo is looking upstream at the west side abutment. The lower photo is looking downstream, that same west side abutment is on the left in the photo, a few more large stones and solid bedrock is on the right (east). There are not enough large stones in the creek bed to have fully spanned the creek to the height of the west abutment, one reason for the supposition that the stones were abutments for a timber dam. Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2015

|

We don't know how long the mill was in operation. Drummond died of cholera in 1834 and we know that by 1841 a sawmill was being operated here by a fellow named Mathewson - "Mathewson's Saw Mill" shows up on an 1841 map (Burrowes, 1841) in this location. Sometime after that the site appears to have been abandoned. Given the low flow of water, it wasn't an ideal mill location, the economics were likely marginal. When the site was abandoned, all the useful material (saws, belts, pulleys, etc.) would have been removed. Planks used to built the sawmill would have been repurposed. The same would go for any cut timber such as that used for the dam. By the mid-1800s, all that was left at the site were the stones, perhaps leading someone to believe they'd been the start of a lock.

The 1833 and 1841 maps, and the stones, are not the only evidence that a sawmill used to be in this spot. Clear evidence of an operating sawmill in the form of wood slabs, the rejected side cuts from sawn logs, litter the bottom of the Peterson Creek. Those slabs provide clear evidence of what the stones at the site were all about – not a lock, but rather a sawmill.

|

Your First Clue

Your first clue that a sawmill used to be located at the head of Peterson Creek are sawn planks such as these that are on the creek bed. This plank is located about 400 metres downstream from the old mill. You'll see these (of varying sizes) downstream from most old sawmill sites.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2015

|

***************

The location of this old mill was brought to the author's attention back in the early 2000s by Jonathan Moore, an underwater archaeologist with Parks Canada. Jonathan noted the location of the mill on an 1833 map. He was involved at that time with underwater archaeological investigations on the Rideau Canal. However, while old mills are very interesting and significant to the history of the Rideau region, they were outside his official mandate from Parks Canada to investigate. So Jonathan and Bruce Bennett, another member of the Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology team, would investigate some of these sites on their own time, using Bruce's small inflatable boat. The author accompanied Jon and Bruce on several of these "Rideau Rambling" trips.

In late October 2004, a Rideau Rambling trip was done to look at several old mill sites on Opinicon Lake. The Drummond mill was the last site investigated on that day. There was a bit of uncertainty as to the exact location, but as we progressed up the stream, the wood slabs lying on the bottom of the channel were a clear clue that we were in the right location and that the old mill site was upstream. And then, similar perhaps to people travelling up the stream 150 years ago, when we reached the head of the stream, the stones became visible. Clear evidence of a dam, or perhaps for those unfamiliar with early dam and lock construction, a dead lock. At the time, the tale of the dead lock wasn't known, but it was still a very interesting spot.

|

The Upper Dead Lock Stones

Jonathan Moore poses for scale on top of the Dead Lock in 2004.Photo by: Ken W. Watson, 2004

|

The Original Navigation Route

Long before the someone coined the name Dead Lock, this area was part of the native travel route from Kingston. This has been previously mentioned, that since part of the area between Upper Brewers and Jones Falls wasn't navigable, that natives travelling by canoe from Kingston to the Rideau travelled via Loughborough and Hart lakes. This will now be explained in some detail. To understand why this route was used, we have to go back to a point in time prior to a mill dams being built at White Fish Falls and at the Round Tail, a constriction in the channel of the Cataraqui River just north (upstream) of Upper Brewers.

|

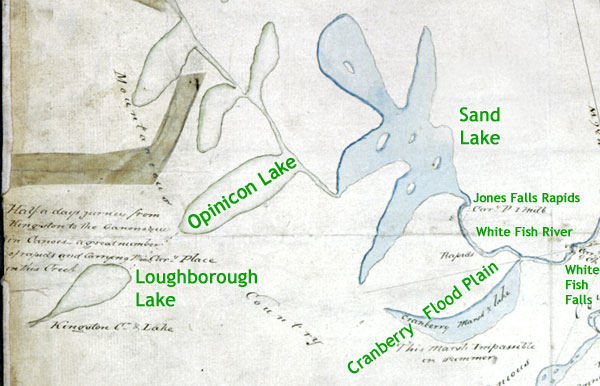

Pre-1805 Watersheds in the Hart Lake area

This map shows the original watershed divide between the Cataraqui and Gananoque watersheds (green dashed line) and the native canoe route (red highlighted). Hart Lake and Opinicon Lake were part of the Gananoque watershed, not the Cataraqui as they are today. The head of the Cataraqui River was Loughborough Lake at today's Battersea. The original Dog Lake (the deeper side of today's much larger Dog Lake) also contributed to the Cataraqui River. The native canoe route from Kingston is shown by the red highlighting. Two very significant locations, White Fish Falls and the Round Tail are also shown in red. The Cranberry Flood Plain is made up of the Cranberry Flood Marsh, an original small Cranberry Lake and the Cranberry Marsh. Refer back to this map as you read the text description below.

|

Prior to mill dams altering the watersheds, Opinicon Lake and Hart Lake were part of the Gananoque watershed. Flow from these lakes went into Sand Lake and from there to the rapids at Jones Falls, the head of the White Fish River which flowed to Lower Beverley Lake and from there to the Gananoque River. The reason for this is that the connection to the Cataraqui River that we have today, didn't exist back then. The section on the map labelled "Cranberry Flood Plain" was dry in summer, not navigable by canoe.

The main native travel route from the Ottawa River to the St. Lawrence River and Lake Ontario was via the Gananoque River, travelling via Sand Lake, down the White Fish River to Lower Beverley Lake and down the Gananoque. This is the route first mapped by a European explorer, Lt. Gershom French in 1783, who was led by a native guide.

However there were reasons to have a route from Kingston to Opinicon Lake. It was a short-cut for natives coming to the mouth of the Cataraqui River, the location of today's Kingston. Plus the route featured two lakes containing Lake trout, Dog and Loughborough lakes. Those lakes were also staging grounds for spring and fall bird migrations, providing excellent hunting grounds. So it was a well used travel route.

The Cataraqui Flood Plain, an area now flooded by 17 feet of water from the dam at Upper Brewers, is an overflow channel for the former White Fish River. The original topography in this area has been filled in with sediment over thousands of years, making it fairly flat, a plain. At summer levels in the pre-dam era, there was no water flow over this plain from the White Fish River. That river went through today's Morton Bay on its way to Lower Beverley Lake. Surveyor Lewis Grant's 1795 map of the area, in reference to the Cranberry Flood Plain, puts it succinctly "this marsh impassable in summer." Grant's maps also notes the route from Kingston to Opinicon Lake, "Half a days journey from Kingston to the Gananoque [Opinicon Lake] in canoes, a great number of rapids and carrying places on this creek." His map shows the end of Loughborough Lake (called Kingston Lake on his map) with a dashed line connecting it to Opinicon Lake.

|

Lewis Grant's 1795 Survey Map

The blue shaded sections are those areas that Lewis Grant actually visited on his survey. The unshaded outlined areas were "taken from an Indian Plan of the River Gananoque and the adjacent country." It only gives us a hint of the native canoe route through Hart Lake, a dashed line connecting Loughborough Lake with Opinicon Lake.

Section from "Sketch of the Ganonoque" by Lewis Grant, 17th June 1795, Archives of Ontario, AO 1532.

|

Those travelling by canoe along the Cataraqui River from Kingston would have had to portage the Cataraqui Falls, then get over small rapids at Jack's Rifts (head of today's Colonel By Lake), Billidore's Rifts (head of today's River Styx), then rapids at Lower Brewers, Middle Brewers and Upper Brewers. There were likely more rapids between Upper Brewers and the next known set of rapids at Battersea, one of the outlets of Loughborough Lake and the head of the Cataraqui River. That "river" was more of a creek, there was shallow water in many spots.

Water travellers going to the Rideau would have traveled down Loughborough Lake Creek to Hart Lake and then through Hart Lake to its outlet at the head of Peterson Creek. Today a short portage skirts the top of the creek, but the natives likely pulled their canoes over this spot. Today the stone remains of the old dams litter the channel, making a bypass portage necessary. Then they would have canoed down Peterson Creek and into Opinicon Lake.

The first European to travel that route may have been Samuel de Champlain who is reported to have travelled up the Cataraqui to Loughborough Lake in October 1615. At that time the Hurons and Iroquois were at war. Champlain was travelling with the Hurons and assisted them in a battle with the Iroquois in the northern U.S. His knee and leg was injured and he was unable to walk. On their return to Lake Ontario, Champlain tried to convince them to take him down the St. Lawrence to Montreal. They didn't want to do this but a small party of natives took Champlain up the Cataraqui River and after spending a month hunting for birds, deer and other game they returned home (overland to the Lake Simcoe area).

There is some dispute about whether Champlain did in fact follow this route, but the route would have been known to the Hurons and other native groups that used the Rideau as fishing and hunting grounds, as well as a travel route between the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers. Our first documented information about this route is Lewis Grant's 1795 survey map and he got his information for this section of the country from local natives (he only mapped the Gananoque up to Sand Lake).

The watershed was about to change due to man's activity. In about 1803, brothers Lemuel and Carey Haskins built a dam and a sawmill at White Fish Falls, the location of present day Morton. This backed up water in Morton Bay, then a deep canyon. The Haskins had a problem though, they wouldn't have been able to get much more than about a 7 foot head of water on their dam at White Fish Falls. The reason for that is that at that level, the backed up water started flowing over the Cranberry Flood Plain on its way to the Cataraqui River.

At some point prior to 1816 (likely closer to 1803 than 1816) they traced their escaping water to the Cataraqui River and built a second dam at the Round Tail, a narrow rocky spot through which the Cataraqui River flowed. When surveyor Lt. Joshua Jebb, R.E., mapped this section in 1816, he canoed over it, noting that the dam at the Round Tail had backed up a 6 foot depth of water over the marsh. His 1816 map is telling though, he called the area of today's Whitefish Lake "land overflowed." Surveror Reuben Sherwood noted this change in his 1807 survey of Pittsburgh Township, stating "I find that the flats of land along the Kingston Mill stream [Cataraqui River] thro' this township all flowed [overflowed] owing to the abundance of water which has changed its course from the Gannannockway River to this [Cataraqui River] since Steven's [Haskins] built his mill in South Crosby ..." It's unclear from his statement if the dam at the Round Tail was in place at that time since the main diversion of water was from Haskins' dam at Morton.

Even after the Cranberry Flood Plain was flooded by the mill dams, becoming known as the Drowned Lands, the native travel route via Loughborough and Hart lakes would have still been used for hunting and fishing in that region and even perhaps to avoid the very long portage around the Jones Falls Rapids or travelling through the somewhat forbidding Drowned Lands. Suffice to say that Peterson Creek has been used as a travel route for paddlers for many (many) years.

You can visit this area today, most easily by canoe or kayak. A minor problem is that man isn't the only dam maker, nature's dam making experts, beavers, continue to try to block off the Lower Dead Lock. That beaver dam (which is opened up periodically) can present a challenge to a power boat (as can the shallowness of the stream upstream from the Lower Dead Lock). The entrance into the Hunter Mill Pond also often has a beaver dam blocking the entrance, but it is easily portaged.

My Paddling Guide 5 covers the area of Opinicon Lake including two Off The Beaten Path trips - one into Hart Lake and one into Lower Rock Lake. See: Watson's Paddling Guide 5

Sources:

Bolton, Daniel, Captain, Senior Royal Engineer Rideau Canal, "No. 4. Diagram of the Townships through which the Rideau Canal passes from the Narrows to Brewers Upper Mill shewing the Lakes which falls into the same", 28th Oct., 1833, Library and Archives Canada, Microfiche 21772.

Burrowes, Thomas, “Rough Plan of the Lock, Dam &c. at Davis' Mill” n.d., Library and Archives Canada, NMC 130287.

Burrowes, Thomas, [Map of Pittsburgh Township], 14 May 1841, Queens University Archives.

Leffel, James & Co., "The Construction of Mill Dams", James Leffel & Co, 1874.

Geological Survey of Canada, "Report of Progress, 1871-72, 1872, Dawson Brothers, Montreal

Grant, Lewis, "Sketch of the Ganonoque", 17th June 1795, Archives of Ontario, AO 1532.

Patterson, Neil A., "Opinicon, The Ghost Town", n.d., Chaffey's Lock and Area Heritage Society.

Price, Karen, “Construction History of the Rideau Canal”, Manuscript Report 193, Parks Canada, 1976, digital edition, Friends of the Rideau, Smiths Falls, Ontario, 2008.

Queens University Biology Station Wikipedia entry, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Queen%27s_University_Biological_Station, 2015

Spence, Hugh S., Phosphate in Canada, 1920, Canada Department of Mines, Ottawa.

Tulloch, Judith, “The Rideau Canal: Defence, Transport and Recreation”, History and Archaeology 50, Parks Canada, 1981, digital edition, Friends of the Rideau, Smiths Falls, Ontario, 2009.

Watson, Ken W., "Engineered Landscapes, The Rideau Canal's Transformation of a Wilderness Waterway", 2006, Ken W. Watson.

Wright, Henry, per comm., 2015

|